A Young Man prepares for War

Young Roger Orrell is a handsome man by any standards. Had he been born somewhere else but close to the mills of East Lancashire then his film star looks would have meant a more lucrative career than being a labourer in the local paper mill. At the outbreak of the Great War Roger is 20 years old. Young Roger is in love and before this war was declared felt his future was mapped out. He knows that escaping from the relatively poor financial circumstances of industrial Darwen is unlikely, but he accepts that situation as long as he can marry his beloved Nellie, a weaver in one of the local cotton mills. One thing he also accepts and without question was that as war has been declared he must go and fight. The urgings of his local contemporaries and management of the mill, plus the even greater pressure from the clergy in the pulpit at his church every Sunday, leaves him in no doubt that the cause was right and just and he has to do his duty. He can risk going to war far more than he can face walking the streets of Darwen as a fit able young man that has not enlisted.

As soon as he is able Roger joins the army and is initially enlisted in the Somerset Light Infantry and starts his training at their barracks in Taunton, Somerset. He is not there for long and is transferred to the Royal Irish Regiment and becomes Private Roger Orrell No: 896 of the 5th Battalion. The bare facts of this are interesting to me and are a coincidence in that I now live near Taunton after living most of my life where Roger did, and my wife’s family are from Ireland. Other than that, I cannot add anything as to why Roger ended up in an Irish regiment so far away from home, rather than being sent straight over to France after initial training. For Roger this seems to be the most exotic of postings to his young mind, but the reality is that conditions in Ireland prove to be harsh. British soldiers are not overly welcome, the political climate is gearing up towards an uprising. Leaving the training barracks is a rare occurrence so the posting to Ireland is a massive culture shock to Roger.

The exotic part of all this is the train journey to Liverpool and the crossing of the rough Irish Sea by boat to Ireland. That journey is a long distance and is the farthest Roger has travelled from his home town of Darwen. It is an exciting time for him to escape the narrow confines of the small mill town. Back home in Darwen the farthest he has journeyed would have been a tram ride into the neighbouring larger town of Blackburn. Even then, that is mostly taking the shorter distance to Ewood Park to watch Blackburn Rovers on the Saturday afternoon he always has free after working in the paper mill Saturday morning. Other than this brief foray outside of the Darwen boundaries he occasionally does ride the tram to the top of the hill just past the cemetery and walk over the moors to Edgeworth to see some of his Orrell relatives, to whom he has a close attachment.

The 5th Battalion Irish regiment were formed at Clonmel at the start of the war and they were destined to be sent to Gallipoli after their training. Training for Roger and his colleagues involves a lot of live ammunition practice and of course the cold steel of bayonet drills. His training does not last long as in early April of 1915, Roger Orrell is involved in a training accident involving live ammunition that leaves him seriously ill with a perforated bowel. The condition is assessed in Ireland and is deemed to be so serious that rather than leave him in Ireland, a long way from his Lancastrian home, he is shipped back as soon as is practicable to the UK. He begins to be treated and kept as comfortable as possible at the Moss Bridge Hospital in Darwen, at that time being used as a military facility for wounded servicemen. In the hospital at Moss Bridge Roger comes face to face with the reality of fierce combat in the actual theatre of war. He now realises why the troops were not home for Christmas, the war he now knows is not a game, but a place of horrific and senseless slaughter.

During his time at the hospital there arrives by train a contingent of Belgium and French wounded soldiers and it is this connection with the actual front line that leaves him in no doubt about the atrocities of war taking place on the continent of Europe. Ironically Roger himself has never reached the front line of combat but tragically had received similar injuries while awaiting his turn to serve at the front. Over many weeks Roger’s condition does not improve and he bravely endures a painful and ultimately fruitless fight for life for many weeks, before he finally dies on Thursday 15th July 1915, his family at his bedside, and attended by the nurses who provided such wonderful care in that hospital, much of which was given over to the soldiers from France and Belgium. He dies ultimately from septicaemia, suffering horribly for many weeks, to the distress of all those around him.

He has had the best possible care available for the times and thankfully does not have to suffer in a field hospital hundreds of miles from home. Rogers body is taken to rest at the home that he had shared with his sister and mother in Redearth Street, Darwen. As is the custom he is placed at repose with the family in the front parlour until the day of his funeral on the following Monday. The town of Darwen has already witnessed many funerals in the course of the pursuance of the war, but Roger’s service and procession is an outstanding tribute to a fine young man, one who was as well respected and loved as anyone in the town. His procession to his last resting place in Darwen Cemetery brings the town to a standstill. Any of the wounded soldiers from the Moss Bridge Hospital that were able to walk, line up outside the house on Redearth Street and followed the cortege to the cemetery. Roger’s coffin and hearse are completely covered with floral tributes to Roger. When the procession has made its slow progress up Bolton Road arriving at the gates of the cemetery, it is first of all met by twenty tearful nurses from the Moss Bridge hospital, all of whom have either treated the young man or been touched by his resilience and no doubt also his attractive looks and personality. Standing immediately behind the group of nurses and leading the way to the graveside are many uniformed soldiers, ones from the hospital that could not make the walk behind the cortege and had arrived by tram, alongside any that were home on leave at this time. There is a large contingent from the Irish Regiment. It is a colourful, impressive, though solemn scene, as the party moves through the open wrought iron gates, winding the way around the narrow paths to the graveside, a short distance up the hillside. Now after this display of respect the trams and traffic can once again use the main road in and out of Darwen.

Just opposite the cemetery gates today is a small section of preserved tram rail, a small reminder of the times that Roger lived in back in the early part of the 20th Century. The Reverend J. Hodges conducts the final service at the graveside, a grave I have visited often and one that is touchingly maintained by the children of a local school who have adopted it into their care. My great grandmother Sarah Atherton is heartbroken at the death of her brother but she still has more tragedy to come as her little boy Roger would die four years later in that road accident.

In the local paper, the Darwen Advertiser on the 23rd July 1915 there was a small notice inserted – it read:

Roger – In memorial from your sweetheart Nellie.

I have not been able to trace who Nellie was, other than the possibility that she was Nellie Entwistle, a possible cousin of Roger who lived and worked as a weaver in Darwen.

Did Nellie ever marry? Perhaps not. In my youth, my home town of Darwen was filled with elderly spinster ladies who never found love again after losing their fiancés in the Great War. Many of these lived together as if they were sisters and indeed many were actual fleshly sisters. These ladies were content, gentle, resigned women. It seemed they all shared a common sadness, a life unfulfilled, a situation thrown into their lives that they could never move on from. If truth be told they felt guilty if they even had the thought that they should move on with their lives. I really hope Nellie was not one of them but I suspect in view of what I witnessed among such women that she probably was – so very sad.

Written and kind permission given to put on our website by Neil Atherton

The original website by Neil Atherton click on the link below

A Young Man prepares for War

FODC July 2023

Darwen soldier who kept going back for more is remembered

Our Chairman Tony Foster reveals more about a persistent war hero

THERE were heroes aplenty in the Great War. Most were recognised with a medal; some just faded away. Few were as determined to do their bit as Darwen lad John Farnhill.

He was wounded in the Boer War and struggled with serious illnesses almost throughout the Great War. Not many soldiers would have been discharged as medically unfit three times.

He was just 19 when he signed up with the East Lancs Regiment and saw action in the Boer War. After two years in the thick of the fighting he was discharged as medically unfit for the first time after sustaining a badly deformed left hand from a bullet wound.

He married a Darwen lass, Mary Elizabeth Gavagan, and worked as a labourer at the paper mill close to his home in Astley Street.

But he missed the adventure and the danger.

As soon as the Great War erupted he tried to sign up, but they took one look at his mangled hand and turned him down flat. By the following February things were getting desperate.

Aged 35, he tried again. This time they ignored his disability and a month later he was in France as a driver with the Army Service Corps.

Later that year he was admitted to hospital suffering from severe lumbago and in November he was back in hospital with tuberculosis.

He was very ill for several months before, in June 1916, he was discharged from the Army a second time.

He had been left very weak but his determination to have another crack was undimmed. In late November 1917, he again joined the ASC and a few weeks later he qualified as a lorry driver.

In early April 1918, he began coughing up blood. He was short of breath. He was weak and had lost weight. The TB that had hit him two years earlier had returned.

He was sent back to England in August 1918, as the Germans were on the run after their final offensive earlier that year had collapsed.

John Farnhill wasn’t going anywhere though and he spent several weeks in a military hospital in London where his condition was assessed as being “attributable to active service in France.”

He was discharged from the Army for the third time in early October and spent the next two months at home where he died on December 4, 1918, a couple of weeks after the Armistice. He was 39.

Mary was left to bring up five children. Her sister Margaret had married John’s brother Edward and they had 16 children.

Their great nephew Albert Gavagan, secretary of Darwen Heritage Centre, wrote to the Commonwealth War Graves Commmission who have now agreed that Driver Farnhill should have an official headstone over his grave in Darwen’s old cemetery.

There can’t be many soldiers who have been discharged from the Army three times. He is certainly one hero who shouldn’t be allowed to just fade away.

FODC July 2020

Darwens Link to Anne Frank

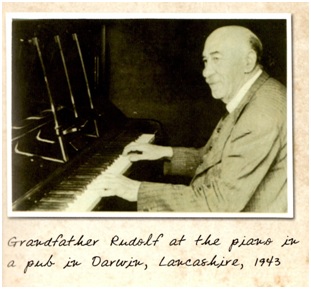

It started with a book I was reading. In it was a photograph of an elderly man playing the piano and the caption said, “Grandfather Rudolf at the piano in a pub in Darwin (sic), Lancashire 1943”.

The book was, ‘The Promise’ by Eva Schloss and Barbara Powers. The book tells Eva’s story and how she survived Auschwitz. Along with another book, Eva’s Story by Eva Schloss and Evelyn Kent I have been able to piece

Rudolf’s story together and along the way discovered a link to Anne Frank.

Rudolf and Helene Markovits lived a comfortable life in Vienna, Austria with their two daughters, Elfriede (known as Fritzi) and Sylvi. They were an ordinary Jewish family who eventually had to leave Austria when life became too difficult and harsh for Jews. Fritzi and her husband, Erich, moved to Holland with their children Heinz and Eva (of Eva’s Story). In 1938 Sylvi and her husband Otto Grunwald moved to Darwen, Lancashire. Otto was an expert in a new process called Bakelite and persuaded the Government he could be of some use in the development of a new product called Perspex. Consequently he settled in Darwen and subsequently changed the family name to Greenwood.

In 1939 Otto and Sylvi were able to send for Rudolf and Helene. The whole family settled in Earnsdale Avenue. I believe that Helene was a dressmaker, Sylvi possibly ran a snack bar, Rudolf played the piano and Otto continued his work in plastics.

Meanwhile in Holland Eva’s family didn’t fare as well. The family lived in Amsterdam and were contempories of Anne Frank and her family. Like the Frank family, Eva also had to go into hiding to escape Nazi arrest. Also like the Franks, they were discovered and in May 1944 ended up in Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp. In her book Eva tells of the horrors she and her mother suffered. But they did survive and made their way back to Amsterdam to await news of Erich and Heinz. Otto Frank did the same and small groups of Jewish survivors waited together for news. As we know, Otto was the only survivor of his family. Eva’s father and brother failed to survive.

In Eva’s book she talks of visiting Rudolf and Helene in England. A friend of mine who lived opposite the Greenwoods in Earnsdale Avenue remembers the day they moved in and also remembers Fritzi’s visit.

Back in Amsterdam Otto Frank and Fritzi, Eva’s mother, become close and in 1953 they married. They spent the rest of their lives telling the world the story of Anne Frank and her diary.

Eva married and settled in North London, but didn’t tell her family her story until 1986.

So there we have it – Rudolf and Helene Markovits’ son-in-law was Otto Frank and so they were, posthumously, step-Grandparents to Anne Frank.

Rudolf and Helen are buried in the Eastern Cemetry in Darwen. I have been informed that the family possibly left Darwen after Helene’s death in 1963, but I don’t know much more. Otto and Sylvi’s sons, Tom and Jimmy have both died but Tom did have children, Caroline and Johnny.

I have located Rudolf’s and Helene’s grave and paid my respects to them.

What started with a photo ended up being a fascinating story and a snapshot of bygone times.

Helen Thomas April 2012

Pte Alex Done: The first soldier buried in Darwen Cemetery

THERE are almost a hundred war graves in the two

Darwen cemeteries, most of them marking the last resting place of members of the armed forces who died during or soon after the Great War.

Of course, hundreds of Darwen soldiers, sailors and airmen died in that conflict, the first in which combatants were killed on an industrial scale.

Most are buried where they fell, in corners of foreign fields. Nearly all the ones interred at Darwen died back home from their wounds, disease or sickness.

The first burial here took place just four months after Britain mobilised on August 4, 1914. Private Alexander Done, who lived in Lord Street and who had married Sarah Turner that June in Railway Road Methodist Church, was a reservist and joined his regiment, the Loyal North Lancashires, at Preston the morning following mobilisation.

Less than a month later he was fighting in France; by early December he was dead. His wife was left to grieve and bring up their daughter, Alexandra, conceived just before he answered his country’s call.

The funeral was a very grand production. “Never before in the history of Darwen has there been such an affair,” said the local paper. Everyone was there and Darwen folk turned out in their hundreds to pay their last respects. Looking back now, nearly a hundred years later, it is clear that the occasion was hijacked by the popular campaign of the time which encouraged every young man to join up.

The Darwen News wrote of Pte Done’s “loyalty and devotion”. He “heard the call of his King and saw his country’s needs”. He “has given his life for honour and freedom”. His death “was full of lustre and splendour.” Yeah, right. And then came the “advert”. “Private Done’s death is a challenge to every able-bodied youth in Darwen; his sacrifice, his untimely end make a call upon his fellow townsmen. Need the picture be drawn further?”

The vicar of St James’, the Rev J Blackburn Brown, took over the whole show after the sounding of the Last Post. He didn’t pull any punches. “Are we at home doing our duty? Are we doing all we can?” was his theme. It’s enough to say that any young man there on that desperately sad occasion would have held his head in shame if he had not already “answered the call.” The vicar even had the gall to tell those assembled on that wet, wintry afternoon that as Pte Done lay wounded he called out: “Oh, if we had more men; if only we had more men.” Really?

The Rev Blackburn Brown warmed to his theme in the next parish newsletter. In a report of Private Done’s funeral he rages: “The cowardly, the selfish, the idle and the self-indulgent are not doing their duty at this critical time … We say deliberately that it is a sin and a shame for any man who stops at home for any reason, however good, to do simply nothing for his country.”It was a call to arms repeated by politicians, civic leaders, writers and poets in the early months of the Great War. But slowly, as the desperation of year after year of trench warfare and wholesale slaughter took hold of the country, the rallying calls became more muted.

The early confidence of “It’ll be over by Christmas” and “Don’t miss the fun, lads,” became obscene jokes.

Alex Done, a shunter on the railways, was 29 when he reported for duty early that August. Within a few weeks he was in the thick of the fighting in the early major engagements of the British Army, the battles of Ainse and Ypres. He was wounded in November and brought home for treatment. By early December he was dead.

At the time of writing, the daughter he never knew, was living in Darwen as a sprightly 96-year-old.

Alex Done’s grave is in the northern corner of Section 2, just behind the children’s playground.

Harold Heys: October 2011.

A true champion of Darwen

Unveiling: Sunday, October 9 at 2pm

Darwen emerged slowly from a scattering of smallholdings and farms to became a village and then a thriving town. A lot of good men – and women – gave their time and their money over the years towards keeping it firmly on the map as an industrious and thriving community.

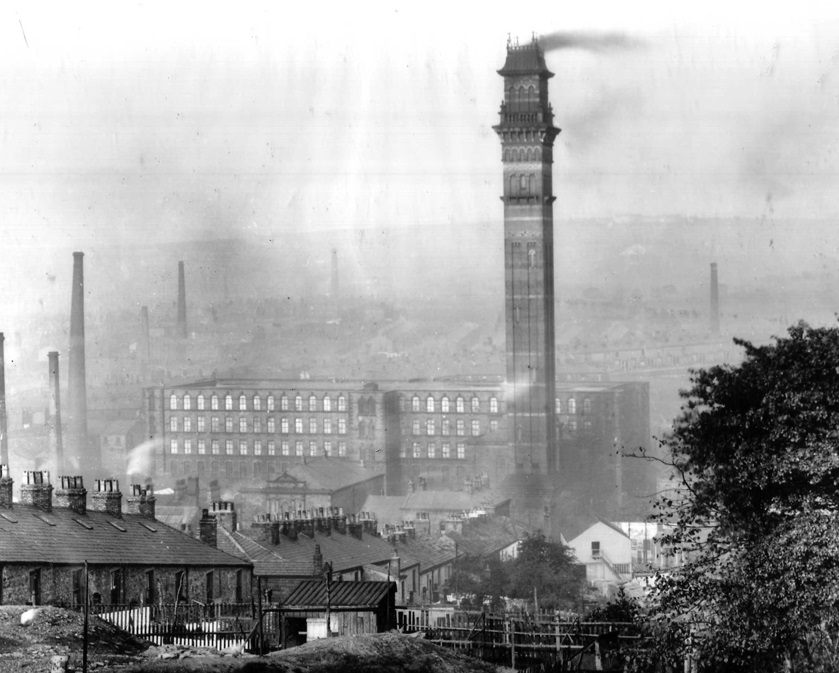

One man more than most – Eccles Shorrock, who built the magnificent India Mill and its world-famous chimney.

Shorrock, who live for most of his life at Low Hill, Bury Fold, was a great benefactor to the town. He was to the fore when Darwen was crippled by the cotton famine 150 years ago, but his efforts eventually led to bankruptcy and a breakdown and he spent his last few years in an asylum in Edinburgh. He died in 1889 and his loss was described in the “Darwen News” as “a merciful release.”

Eccles Shorrock was buried in the family vault in Darwen’s old cemetery, close to the mound on which the Non-conformist chapel once stood. But such was the stigma that mental illness once had the grave of one of the great Darweners was not marked with even a modest headstone.

Thankfully, these days that stigma is being swept away and caring communities and families and the NHS do their best to help people with mental problems.

Monday, October 10 marks World Mental Health Day and on the previous afternoon the Friends of Darwen Cemetery will unveil a headstone to mark the contribution that Eccles Shorrock made to the town and especially his legacy of India Mill whose elegant chimney can be seen through the cemetery trees away to the north.

India Mill have made a donation to the headstone and Blackburn with Darwen Council’s mental health department have made a similar donation from the

funds they have set aside for World Mental Health Day.

It was at noon on a cold and windswept Tuesday in early October 1889 that Eccles Shorrock was laid to rest. The funeral was strictly private but hundreds of local folk lined the route to Darwen Cemetery from Low Hill and thronged the cemetery entrance.

There was a hearse, two carriages with his widow and eight children, and two private carriages of their friends the Huntingtons. Four of the Shorrock servants acted as bearers and the interment followed a short service in the nearby Nonconformist Chapel.

On Sunday, October 9 at 2pm the chairman of the Friends, Coun. John East, will introduce proceedings and Tony Foster and I will talk briefly about the life and death of Eccles Shorrock and the history of the family vault. The Rev Geoff Tolley will dedicate the headstone and the Mayor of Blackburn with Darwen. Coun Karimeh Foster will unveil it.

HAROLD HEYS September 2011

Mr Joseph Turner

Joseph Turner was born in Manchester on 15.5.1855. His obituary in the Goole Times states that he came from a family whose members had been involved in paper-making for many generations, and indeed, the 1841 lists his grandfather, also Joseph, working as a paper-maker at Stretford, as is his father John on the 1851 census. John was still a paper-maker in 1861 but now living with his wife and young family at Hayfield in Derbyshire. By 1871 they had moved to Glossop, and young Joseph, aged 15, gave his employment as paper-maker’s apprentice.

At some time during the 1870s, Joseph moved to Darwen, and married his first wife Martha. In 1881 he lived at Watery Lane with Martha and their daughter Emily. Sadly Martha died in 1886, but Joseph married again shortly afterwards, to Priscilla Appleyard.

Although Priscilla was born near Filey in Yorkshire, her family lived in Darwen for some years and Priscilla was a school teacher before her marriage.

The 1888 directory for Darwen lists Joseph Turner as a Mill Manager, and it appears he was involved with Darwen Paper Mills, before moving to work at the paper mill at Feniscowles.

In 1898 he moved to Rawcliffe Bridge near Goole, to take over the paper mills there, being one of the shareholders of the company formed to acquire the property.

This seems to have been a very successful enterprise, and was at one time the largest employer in the district, employing about 200 people.

Although Mr Turner lived at Ivy Villa in Rawcliffe Bridge from 1898 until his death on 27.9.1923, he is buried in Darwen Cemetery. The local papers in both Goole and Darwen carried an account of his funeral which clearly demonstrates the high regard in which he was held.

He left an estate valued at around £50,000.

One can only surmise that he wished to be buried in Darwen as it represented the start of his successful managerial career, and that he had many happy memories of the town. His grave stands proud, if somewhat overgrown, over to the right from the path leading up into the cemetery from the Lark Street entrance.

The help of the staff at Goole Library and Darwen Library is gratefully acknowledged.

Tony Foster April 2011

Greater Love Hath No Man …

DARWEN’S sweeping moorland has always had a rugged attraction, especially in the summer months when families take to the footpaths and tracks which meander through the surrounding hills to enjoy both the exercise and the fresh air.

In winter, however, the moors can be inhospitable and dangerous, especially if walkers are not prepared for the weather which can change in minutes.

It was much more perilous many years ago when footpaths were rough and ready and when danger from deep gulleys and old mine workings lurked at every turn.

It was just a few days before Christmas, 1917, when three local lads decided on an afternoon walk on to the moors to the south-west of Darwen after Sunday School at St Barnabas’. It was both adventurous and dangerous for they set off in the face of the first flurries and swirls of the most severe blizzard the town had seen for years.

All three were found dead in the snow drifts during the next few days of frantic searching by police and volunteers.

It was a tragic story made even more poignant by the revelation of a selfless act of courage by 16 year-old Ralph Bolton…

The joint funeral and the formal inquest were over in days and the tragedy was soon pushed into the background as the prospect of another long year of war dominated every part of life – and death – both locally and nationally.

The three lads were William Cooper Longton of Culvert Street, which was close to the church, just 18 and due to join the Army within a few weeks; Ralph Bolton, of Maria Street and his ten-year-old cousin James Bolton of Princess Street – where Mayfield Flats now are.

Why did they set off for the threatening moors when it would be dark in an hour and in weather which, according to the Darwen News was “wild in the extreme” and with “their only shelter the heavens above”?

The paper said: “It must forever remain a mystery.” But, looking back now, with old maps of footpaths to hand, it seems fairly clear that the boys simply took a wrong fork.

William was wearing a blue serge suit and a dark, heavy overcoat; Ralph had a blue serge suit, brown overcoat and leggings and little James wore a black suit and a light top coat. They knew the moors well, but this was precious little protection against the drifting snow and piercing north-east wind.

The alarm was raised that Sunday evening and by dawn a big search was under way. The boys had been seen heading in the direction of Rough Height Farm above Bull Hill Hospital on the southern moors. Snow had drifted up to 10ft and conditions were very difficult.

It was on the Tuesday afternoon that the body of William Cooper Longton was found to the south of Old Lyons farm which was over to the west, on the Cadshaw Brook side of Black Hill and a couple of miles from the safety of Bull Hill.

It seems that he had set off to get help and had reached the farm only to find it unoccupied before pressing gamely on.

On the Wednesday, after a slight thaw, the body of little Jimmy was found

under drifting snow in the lee of a stone wall about 400 yards to the north of the empty farm.

He was wrapped in his cousin’s brown topcoat which had been carefully placed over his own light coat.

Ralph himself, left with just his cheap suit, was found frozen to death about 200 yards away. It seems as though he, too, had set off to get help after making the little boy as comfortable as he could in what shelter he could find for him.

In the pocket of the coat Ralph had wrapped around the child was an emblem bearing the legend: “Fight The Good Fight” and, as the Darwen News report asked: “Had he not done just that when he gave his overcoat to his young cousin?”

On the Saturday the bodies of the three pals were taken from their homes to a moving funeral service at St Barnabas’ where the older boys had been in the Church Lads’ Brigade and in the choir. William had also been the Sunday School secretary.

Hundreds of mourners packed the church and there was no more sad a figure

than frail Mrs Nancy Bolton, whose husband Joseph had been killed in action in France the previous summer and who had now lost her only child at the age of just 10.

Hundreds more lined the route to the nearby cemetery, their sadness

compounded by the desperation of a continuing and bloody war and the selfless heroism and fine example of a 16-year-old boy.

William was buried with his grandparents. The cousins were interred together, just a few yards away.

Ralph’s gravestone bears an inscription taken from the Bible, from John 15:13 – “Greater love hath no man than he who layeth down his life for another.”

Over the years the gravestones of the Bolton lads began to break apart and a few years ago a local stonemason kindly remade the whole grave in white marble with the same inscriptions. Sadly the nearby grave of William Longton and his grandparents is still broken and neglected.

The tragedy was a mystery. But a simple wrong turning in the blizzard looks the likely cause. An uncle of the younger boys and his family lived at Duckshaw Farm above Bury Fold and they might have been heading there.

It would have been adventurous and even dangerous but perhaps not as foolhardy as it had seemed.

As they approached Rough Height a right turn to the footpath through Higher Barn, Meadow Head and Wet Head would have taken them to the safety of Duckshaw Farm before it went dark. From there it was an easy walk home;

down through Whitehall or Bury Fold. Instead, above Bull Hill, they pressed on slightly more to the west – and on to their deaths.

The hurried inquest on the day after the last body had been found discounted the theory that the pals were heading for an uncle’s farm as it was “in the opposite direction.” It wasn’t. Duckshaw Farm, where William Bolton and his family lived, was just to the north of Black Hill and the lads had probably simply taken a wrong turn in the heavy snow as the footpath forked.

A moving postscript to the drama was penned by the writer of a letter to the Darwen News a few days later when local folk were still asking what had made them embark on what had seemed such an ill-advised venture.

“Such confidence, strength of purpose and love of adventure was obviously displayed by these lads and the crowning sacrifice made by one in giving up his overcoat only emphasised the true British spirit which their elders are displaying every day on the battlefields of Europe.”

The grave of the Bolton boys is by the north side of the mound which used to house the Church of England Chapel. It clearly stands out in white marble some 12 metres from the Ashton Memorial at the end of the tarmacadam path which runs south from the main entrance parallel to the main road.

The new headstone and kerbs were erected by

Mark Rule a few years ago after the original gravestones had fallen into disrepair..

William’s grave – he is buried with his grandparents – is about ten metres to the north of it.

Harold Heys April 2011

The Place Family

The first section to be worked on by the Friends of Darwen Cemetery in their first year (2010) was Section C. One of the graves in Section C is that of Edith Bury (nee Place), her husband Edward Bury and one of their daughters Sarah Elizabeth.

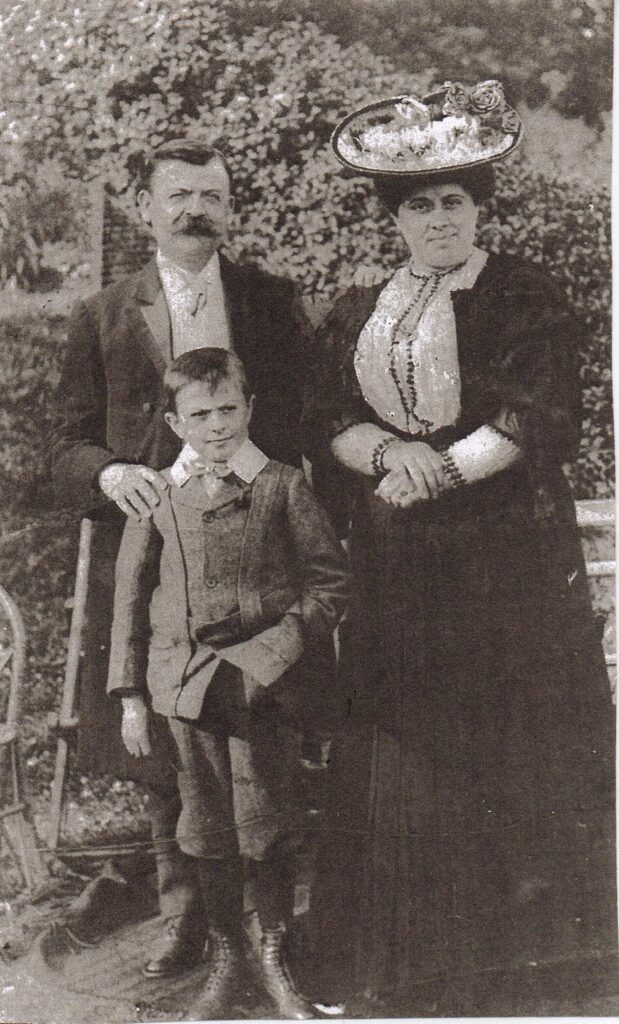

Edward Bury, Edith (Place) Bury with their youngest son Frederick Robinson Bury, Ann’s ‘maternal’ Great Grandparents and Grandfather.

Grave of Edward Bury, Edith and daughter Sarah Elizabeth in Section C.

She was one of the daughters of John Edwin Place Senior who, with his brother William Henry Place were local industrialists. This large red granite cross was toppled in the first round of grave testing but the family had it reinstated by a local monumental mason.

Edith Bury (nee Place)

John Edwin and William Henry’s father Joseph

Place came to Hoddlesden circa 1832 with his brother John from West Bradford near Clitheroe and owned coal mines in and around Hoddlesden. They were also cotton manufactures with mills and a weaving shed at Vale Rock, Hoddlesden.

Their company was known as J and J Place. In 1863 the partnership between Joseph and John was dissolved. Joseph took the firm’s colliery business and John the cotton manufacturing.

The company of John Place and Son failed in

1864 and Vale Rock Mill, Hoddlesden was closed.

Joseph Place married Ann Hodgson from Rishton. He was a prominent member of the Duckworth Street United Free Methodist Church and was a Sunday

School teacher. He died in 1881. Their sons John Edwin Senior and William

Henry started work at the age of 14 in the offices of the collieries, where

they learned how to manage the colliery and eventually were taken into partnership.

The No 1 Pit near Vale Rock Mill, Hoddlesden was the oldest of the Place’s workings, but new shafts were sunk between 1860 and 1864 to reach coal and clay for stoneware and a fireclay seam. This Pit reached a depth of 360 feet with two engines, one for pumping and one for winding.

In 1872 the Miners’ Regulation Act was passed requiring managers to be

certified. William Henry gained his certificate aged 24 and remained working as a manager for approximately 17 years. He managed the firms while his brother John Edwin promoted the company and secured sales.

In 1891-1892 Joseph Place and Sons Ltd, sank another shaft at Eccleshill and established a further Sanitary Pipeworks near Goosehouse Lane, Darwen.

When the local Pit was abandoned in 1916 the Works continued to operate

using fireclay from Hoddlesden. The tramways built in 1861 to link the Pit to

the Old Sett End, Roman Road, and modified to New Sett End in 1877 were

used for this and continued in operation until 1938 when some of the coal pits were exhausted.

Grave of John Edwin Place senior, his 1st Wife Elizabeth and 2nd Wife Esther re erected in March 2011

In 1897 Joseph Place & Sons Ltd were registered as a Limited Liability Company by Ann’s Great Great Grandfather John Edwin Place Senior, William Henry Place, George Brindle (Paper Manufacturer) and Robert Clayton (a Cotton Manufacturer from Rishton).

John Edwin Place Senior was married twice, firstly to Elizabeth, nee Robinson, the mother of his six children. She died in 1887. He then married his second wife Esther nee Richards. They did not have any children.

John Edwin Place and Elizabeth’s children were Frederick Robinson Place, John Edwin Place Junior (known as Ted), George Hardisty Place, Edith Place, Ann Isobel Place and Helen Place (known as Nellie Place). He lived at ‘Long Marsh’ and ‘High Lawn’ House and over a period of time lived in property in Railway Road, Richmond Terrace and Hindle Street, Darwen. He was a member of the Belgrave Chapel. He loved music and earlier in his life he had served as organist at the Duckworth Street United Free Methodist Chapel.

It was said that he was a highly respected man of trade and he was one of the earliest members of the Darwen Local Board. He served for a short time as one of the first Town Councillors after Darwen was Incorporated in 1878. Both brothers were Liberals and both served the Borough and County as

Justices of the Peace.

Darwen News July 5 1884

NEW LOCOMOTIVE ENGINE – The new locomotive engine which has been built at Bristol expressly for Messrs. Joseph Place and Sons at a cost of £700 arrived on Thursday afternoon, and was brought on the metals by an ordinary pilot engine. At five o’clock yesterday afternoon a trial trip was made in the presence of the members of the firm – Messrs. W.H. and J.E. Place – and a large concourse of spectators and workmen. The engine presents a beautiful appearance, and is named “Joseph Place”, after the name of the late Mr. Place, who was senior member of the firm.

The engine was tried with an empty wagon, and took all the points beautifully It was run right up in the Goods Station siding, and tried over the various sidings belonging to the works. The level crossing looks rather a dangerous one, but we have no doubt that the firm will see that sufficient gates and protection is made for the safety of the public and conveyances generally. Many of the old women of the village, who gazed on with pleasure, appeared to have got the idea that they would now be able to go to Darwen any time, but, we had better inform them that this engine is only for the specific use of Messrs. Place and Son, running their goods up to the Hoddlesden siding, and very rarely will it be found making a journey to Darwen. We hope, however, that the passenger service will before long be added? to this rather important village.

William Henry Place, the uncle of Edith Bury, was said to be of imposing appearance and having an excellent temper and was very attractive in his manner and ways. He was said to have a keen sense of humour and enjoyed ‘a good story’. As an amateur vocalist he had, when young, one of the finest tenor voices and for three years was choirmaster at St Paul’s Church, Hoddlesden. He was a fine shot at both targets and in the hunting field. He was an enthusiastic sportsman enjoying cricket, football and golf. He distinguished himself as a volunteer in the Lancashire Regiment of Volunteers where in 1875 he received a commission, first as lieutenant, becoming Brevet Tank Major, then as acting Major and after 26 years service he was given the Brevet Rank of Lieutenant Colonel. He married twice, first to Maria Baron Rudd from Thirsk in Yorkshire and second to Millicent Amy Curwen from Cheam. Maria and William Henry lived at Ashleigh House.

William Henrys Grave in Section F

There were no children from either union and William Henry died there in 1919. John Edwin Place Senior died in 1913 and is also buried in the cemetery in Section A. His imposing granite headstone has been toppled.

William Henry is buried in Section F of the cemetery amongst the other well

known industrialists of the town. His memorial is a large celtic cross still

standing on the hillside.

Brent Stevenson Memorials re erecting the grave of John Edwin Place

© Ann Stokes March 2011

A man who devoted his life to God and his parish

If you didn’t know, you would never guess at the humble beginnings of the

Catholic Church in Darwen. It was long before the building of St Joseph’s and

St Edward’s. It was on the steep hill at Red Earth in a building which is now …the Black Horse pub.

Fr Desiderius Vandenweghe Grave

Land was eventually purchased in Radford Street and St. William’s Chapel was built, largely due to the shrewdness and sheer determination of Fr. Meaney from St Anne’s, just off King Street, Blackburn. It opened in 1856.

Travelling from Blackburn wasn’t easy for priests in those days as the roads were very poor. In 1858 Fr Desiderius Vandenweghe was sent to take charge of the Darwen Mission. It was an inspired choice. He was to remain as parish priest until his death on March 26, 1898 at the age of 70.

He is buried in Darwen Cemetery, on the corner of Section D, just by the narrow tarmacadam road. His lead coffin was covered by a polished oak casket with brass fittings and the plate bore a simple inscription giving the deceased’s name and the dates of birth and death. Clergy from the Congregationalist and Primitive Methodist Churches attended and the local newspaper described the funeral procession as “a most imposing one of

great magnitude” and added that the route was thronged with people.

On his arrival in Darwen, Fr. Vandenweghe lodged with a local family in Bridge Street, but he soon embarked on an impressive building programme. In 1861 he went to live in the new presbytery in Radford Street where he planned further parish improvements.

He extended the school rooms at the mission and began a day school for the education of the children of the parish. Over the next few years as the parish

grew in numbers, so did the social and fund-raising efforts. Concerts and tea parties were among the favourite events. The parish was far from insular and

took part in town events and celebrations.

By 1872, the Mission of St. William’s had grown in such numbers that

Fr. Vandenweghe decided that, in order to accommodate everyone at services,

he needed to establish a mission at the northern end of town. Lord Edward Petre, the Lord of the Manor of Lower Darwen, gave an acre of ground for the building of a school to be called St. Edward’s after his patron saint.

St. William’s Parish flourished, so much so that in 1870 a plot of land was

bought near the top of Mill Gap from cotton manufacturer Eccles Shorrock –

the man who built the nearby India Mill – for a bigger church when funds

permitted.

In spite of his own ill health, Fr. Vandenweghe continued to look after both St. William’s and St. Edward’s as no other priest was available to take over at the northern end of town until the late 1880’s.

The new parish church of St Mary and St Joseph was opened on October 15,

1885 by the Rt Rev Dr. Vaughan, Lord Bishop of Salford. The local press made

much of the fact that during those hard times, when work was not easy to

come by, all the sub-contract work without exception was given to local people and so the building of the new church became the main source of employment

for many in the town during that year.

Many local dignitaries, including the Mayor, attended the opening of the

church which was described as “an edifice which is an honour to the Catholic

community and an ornament to the town!” Fundraising continued over the

next years and a new school was also erected.

The impressive headstone at Darwen cemetery is also in memory of two

assistant priests who worked with Fr Vandenweghe. In 1876 Fr. William

Hampson, a native of Farnworth, was appointed his assistant. He worked

untiringly, caring for the needs of the parish and in particular visiting the sick. However, within ten months of his arrival in Darwen, through his visits to sick parishioners, he had contracted typhoid and died at the age of 24. He was

interred at Moston.

Fr Vandenweghe was not a well man, having suffered from heart trouble for

many years and so a second assistant priest was sent to help him. He was

Fr. Peter Kopp from Coblentz on the Rhine. He quickly endeared himself to the congregation, but he too died within a short space of time. His death notice

said that he died of a fever, caught in visitation of the sick. He was 25.

On the morning of Saturday, March 26, 1898 Fr Vandenweghe himself passed

away. He was found lying in bed, with his hands clasped in prayer, having died

in his sleep.

It is doubtful whether any local clergyman has ever worked so tirelessly for

his parish as Desiderius Vandenweghe. Darwen’s Catholic community in the

second half of the 19th century was indeed very fortunate to have his guiding

hand for more than 40 years.

More information is available on the St Joseph’s web site.

www.stjosephsdarwen.org.uk/history.htm

Harold Heys March 2011

The lady vanishes

Walking through the cemetery can be very pleasant, especially on a warm,

sunny day, perhaps with a companion; perhaps with a pet dog. It must be

even more pleasant now that the Friends and their helpers have opened it up considerably and brought in some much-needed tender, loving, care.

But on a cold, damp evening, perhaps with a light drizzle sweeping down from the moors and with the light beginning to fade, it can be just a little eerie for anyone walking the winding, shaded paths alone.

But, if you work in the cemetery, you have to roll up and get stuck in whatever the weather; and even when your imagination and the flickering shadows might be playing the occasional trick.

Do you believe in ghosts or in the supernatural? It’s not a question I like to ask of anyone; I like to steer well away from the topic. But as I was talking to cemetery supervisor Billy Briggs the other morning about clearing some paths. I shivered a little in the icy morning and wondered, almost to myself,

Billy Briggs

whether he had ever seen or felt anything in the old cemetery which had

either excited his curiosity or perhaps sent a shiver down the back of his neck.

Surely, in some 37 years of working in the cemetery, he must have felt, a

little, you know… “Just the once,” he told me, quietly. This is his story.

It must have been over 25 years ago. But the hairs on the back of my neck

still stand up when I think about it. Not that it was really scary; more puzzling,

I suppose.

Arthur Price was the cemetery supervisor in those days. He was quite a

character. He and his wife had a stall on the market. Nice bloke. Anyway,

one morning he gave me a box which he said were ashes and he asked me to

bury it in a certain grave. He said they were the ashes of an elderly lady he

and his wife knew, a Mrs Duxbury. He had agreed with her family that he

would have them buried quietly in their grave in the cemetery. Just here as

a matter of fact.

We had walked barely a couple of yards from the path where we were talking

to the edge of Section D2 by the rhododendron bushes that snake towards

the higher ground. He pointed to an unmarked plot of tired grass and springy

moss.

I’d just dug out a hole, not very deep as the box of ashes was only little.

I was just going to put them in the hole when I sort of sensed someone

standing next to me, just a bit to the right. I looked up because I hadn’t

heard a sound. A woman was standing there. She was dressed normally as

I remember. Certainly nothing unusual. I think she had a small hat. She’d be in

her late 60s, I suppose.

She said: “Are those Mrs Duxbury’s ashes.” I told her they were. I had them

in my hand so I placed them in the little grave and moved back a bit so she

could see them in place.

I looked up and was going to ask her if she felt that everything was in order

as she seemed to have some interest in what I was doing. I was just being

polite. But there was no one there. She had vanished.

It had taken me perhaps three or four seconds to put the box of ashes in

the grave. She couldn’t have gone five yards in that time. But she wasn’t anywhere to be seen. I could see all the way down to the office and across

Lark Street to the park. She couldn’t have gone through the bushes. Much

too thick. There was no one in sight.

Anyway, I finished off and went down to the cemetery office and told Arthur.

He listened carefully and asked me what she looked like. I told him. “I’ll bring

a photograph in the morning for you to have a look at,” he said. And the

following morning he handed me a picture. “Recognise anyone?” he asked.

There were about seven or eight people in the picture, most of them women.

I only needed a glance. I told him: “There on the right. That was the lady I

was talking to. No doubt about it.”

Arthur took the photograph and carefully put it back in his wallet. He told me: “That lady is our old friend Mrs Duxbury. And yes, it was her ashes you were burying up there yesterday.”

Harold Heys March, 2011

Unveiling of the Great War Cross

NEXT time you walk or drive into the cemetery, have a closer look at the Cross

of Sacrifice which is just inside the grounds behind the north lodge and close

to the short stone wall that marks the first boundary of the cemetery.

It’s very impressive.

Similar to scores of war memorials throughout England and abroad, it was designed by architect Sir Reginald Blomfield for the Imperial (later Commonwealth) War Graves Commission. You will see them in Commonwealth war cemeteries containing 40 or more graves.

There are close to 100 in Darwen Cemetery.

There are three sizes of the freestanding, four-point limestone Latin cross, ranging in height from 18 to 32 feet. On the face of the cross is a bronze sword, blade down. It is usually mounted on an octagonal base. The Cross represents the faith of the majority of the dead and the sword represents the military character of the cemetery.

Late last year contractors for the CWGC relaid the stones around the base and the Friends have erected a notice board alongside it.

There is a second notice board by the Lark Street entrance.

Darwen’s Cross of Sacrifice was unveiled at a dedication service on the

afternoon of April 20, 1929. It was known as the Great War Cross and the

order of service noted that it had been erected by the Imperial War Graves Commission “to the memory of members of His Majesty’s Forces who gave

their lives for their country in the Great War, 1914-18 and who lie buried in

the Borough of Darwen.”

Many scores of soldiers, sailors and airmen from Darwen who fought in the

Great War fell in battle and were buried in graves far away from their home

town. The “lucky” ones were buried in Darwen. Many others died of their

wounds in the months and years that followed the end of the conflict.

Others died in the great influenza epidemic that ravaged Europe as the

war ended.

Now, of course, the Cross is also in memory of other members of our

Armed Forces who died in later conflicts around the globe.

The unveiling of Darwen’s Great War Cross was quite an occasion and a

large gathering of the great and the good met by the cemetery entrance

at 3.25 that Saturday afternoon. Among them were members of the British

Legion and other ex-service men, clergy and ministers, magistrates,

councillors and the town clerk, representatives of the Imperial War

Graves Commission and Corporation officials. There was a large crowd, every

one of whom had been touched by the war.

A choir under the direction of Mr John Bentham led the singing of the first

hymn “O God, our help in ages past, / Our hope in years to come.” and then

the Rev. F Bolton said a prayer. The Rev. GW Stacey read the lesson and this

was followed by the hymn “Jesus, lover of my soul / Let me to thy bosom fly.”

Mr EH Wilson of the IWGC officially handed over the War Cross to the Mayor, Councillor Eli Leach, who performed the unveiling. The Mayor’s chaplain, the

Rev. A Bond, gave the dedication and there was a final prayer from the

Rev. J Emrys Morgan.

The impressive ceremony concluded with the Last Post, a one-minute silence, Reveille and the National Anthem.

The cemetery in those days must have been impressive. Sadly, over the

years, the last resting place of many local servicemen – and other residents –

was allowed to deteriorate. Only now, through the Friends of Darwen

Cemetery, is a concerted effort being made to bring some measure of

deserved respect to Darwen’s heroes of yesteryear.

HAROLD HEYS March 2011

The Rev. Philip Graham

BEFORE Darwen Cemetery opened in 1861 it was usual for parishioners to be buried in church grounds. But after that date the municipal cemetery became the last resting place of choice for just about everyone. Churchyards throughout the country were getting full up and the health hazards from many of the old graveyards were becoming a problem. New town cemeteries were badly needed and they were being opened throughout the country in the mid 1800s.

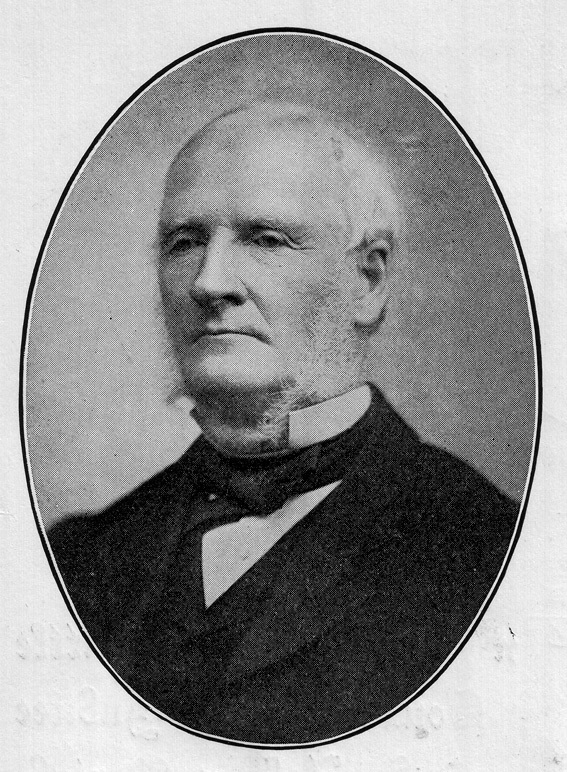

In Darwen there was, however, one notable exception to the new standard. When the Rev. Philip Graham died in the spring of 1887 he was buried not in the municipal cemetery but in his own churchyard. And there he lay for nearly 80 years. The Rev. Graham, born in Cumberland, came to Darwen in 1851 as curate of Holy Trinity Church where he made quite a name for himself. In more ways than one.

Turncroft Hall as it is today

He was friendly with Jane Brandwood, soon, in 1857, to be heiress of her father, uncle and brother who had all been coal merchants and mine owners, but she married widower Eccles Shorrock, a prominent cotton manufacturer and uncle of the man who later built India Mill. Shorrock died on July 23, 1853 after less than two years of marriage to Jane.

The Rev Graham had been moved from Darwen in September 1854 to work as curate at St Marks’ Cheetham Hill and family and local historians reckon he was packed off to cool his heels and his ardour. He stuck it for about 15 months and then resigned his curacy, returned to Darwen, and, in the autumn 1855, married the grieving widow Shorrock who was by then already very wealthy.

Mrs Jane Graham

No more tramping round the mean streets and slums of Manchester for Philip. The Grahams lived at Turncroft Hall in some style and she built for him the rather magnificent St John’s Church on Red Earth Road (as it was then spelt). It was consecrated in the July of 1864; St John’s School on Barton Brow followed two years later. I spent nearly six years there as a child and remember the two school “houses” – Graham and Huntington which was named in honour of another prominent local family,

Jane died after a long illness in the spring of 1867 and already Graham was heavily involved in politics and civic affairs. He was one of the founding fathers of the Conservative Party in North East Lancashire and was every inch the landowner and gentleman benefactor. After his death on May 10, 1887, there were glowing tributes to him in the local Press and in the Parish Magazine.

The memorial inside the church

The probable reason for him being shunted off to Manchester was not mentioned. Eccles Shorrock II had no doubt about the situation and it appears that he and his family were rather miffed that Graham had got his hands on a considerable proportion of the vast riches which might well have fallen into their hands.

The original headstone

Eccles Shorrock II wrote of Graham marrying his uncle’s second wife Jane” immediately after she was widowed” and added: “Rumour had it that the two had been well known to each other before she became Mrs Shorrock. With some feeling, he said Jane had “carried off a substantial legacy after less than two years of the marriage.”

His own mother had died and as a young man he wasn’t impressed with his uncle: “I cannot speak, even now, of my feeling when he took it upon himself to marry again so soon after Aunt Eliza died in 1850, who, though she had never wished me to call her ‘Mother’, had been a true parent to me, kindly, but firm, warm – natured,

giving strongest encouragement to my endeavours, the perfect complement to uncle, who retained a certain aloofness.’By 1869 Graham was so involved with his estate, local politics and various Committees that he gave up his living and was busy enlarging his list of prominent contacts.

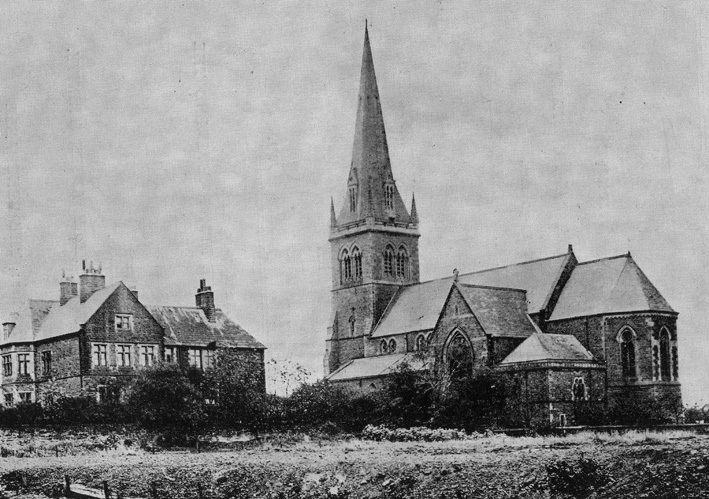

An early picture of St John’s and the vicarage

There doesn’t appear to have been much love lost between Graham, Conservative and C of E and Shorrock, Liberal and Nonconformist. The Shorrocks were very well off industrialists, of course, but times change and within a few years they were descending into rather straightened circumstances. However, all that for perhaps

another day.

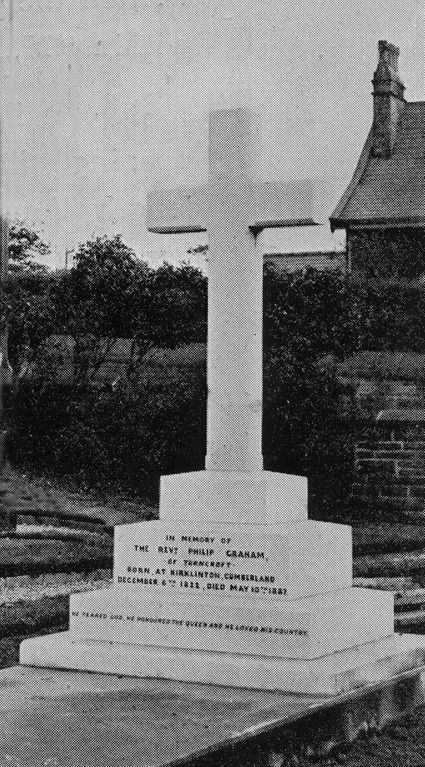

Graham was buried in St John’s Church grounds, just on the north side. There was a fine cross with the line: “He feared God, he honoured the Queen, and he loved his Country.” Three years later his second wife Isabella paid for a memorial in white marble inside the church. They had been married in London ten years after Jane’s death. Special permission for the burial had to be obtained from the Home Secretary and it had to have the assent of the local authorities. The grave was consecrated according to a special form of prayer. It was quite an occasion. Everybody was there.

(Above) The headstone now.

And that is where the Rev. Philip Graham, first vicar and founder of St John’s Church, man about town, benefactor and politician, lay in splendid isolation for the next 80 years…. In 1966, soon after the church had celebrated its centenary, dry rot was rampant in the church and there wasn’t the money for wholesale renovation. It was demolished and the first vicar’s remains and headstone were moved, on September 22, to a new resting place in Darwen Cemetery. You can see it today and you can still make out the inscription. But, of course, the elegant cross no longer sits majestically on top. Elf ‘n’ safety, you see. However, the cross isn’t damaged and sits neatly in the ground in front of the base.

Perhaps one day an entrepreneur or benefactor will find a couple of hundred pounds to clean it up and restore it to its former glory…. The grave is reached from the Lark Street entrance. Through the gates. Turn quickly to the right and follow the ragged asphalt path as it begins to curve uphill for about 40 yards. The grave is by the stone wall in the shade of the line of tall trees. Tony Foster adds: The new church of St John’s did not have a burial ground attached because central government had instructed the Local Board of Health a few years earlier that all graveyards attached to the Darwen churches and chapels had to close for burials that required new grave plots. As the Darwen LBH took some considerable time to find a site and build the cemetery the cut-off date was put back a couple of years. There were Church of England graveyards at St James’ and Holy Trinity and at these Nonconformist chapels: Lower Chapel, Pole Lane Chapel, Belgrave Meeting House, Wesleyan Methodist Chapel in Belgrave Square, Redearth Road Primitive Methodist Chapel and Duckworth Street Methodist Chapel.

By HAROLD HEYS and BILL TAYLOR February 2011

William Dewhurst

OVER the past 100 years or so, a handful of single words will readily conjure up emotions of sadness and tragedy, success and hope for anyone with a taste for history and a sniff for nostalgia. Places. Events. People. Disasters. Just a word; that’s all it takes. How about this dozen for instance: Dunkirk. Abdication. Alamein. Diana. Falklands. Holocaust. Hillsboro’. Beatles, Kennedy, Titanic, Hitler and Elvis. Making a list is interesting and quite a challenge. But it’s likely that the word “Lusitania” will figure on most Top 20 lists of key words. More than 1,000 people died when the German submarine U-20 torpedoed the Lusitania off the south coast of Ireland on the afternoon of May 7, 1915. Close on 200 of them were American citizens and this was one of the reasons why the USA came into the war the following year. One of those who died was a young Darwen lad, 21-year-old William Dewhurst who had spent the previous two years with relatives in Fall River, Massachusetts, a major cotton manufacturing centre which had attracted a lot of textile workers from East Lancashire. Before then he had been a weaver at Bowling Green Mill. William, who used to live in Bolton Road – just across from the United Reformed Church – had attended Culvert School in Watery Lane and was determined, when the First World War broke out, to return home to enlist and fight for his country. He had been a prominent member of St Barnabas Church and a sergeant in the Church Lads Brigade before going off to, first, Canada and then the USA. Most of his old friends from St Barnabas were already in the thick of the fighting. It’s a measure of William’s courage and determination that he readily joined the ill-fated Lusitania out of New York and bound for Liverpool on May 1. The Germans had warned people not to sail on the 32,000 ton ship which they regarded as a legitimate target as, they said, she was going to carry war supplies. She did indeed carry tons of fuses, rifle cartridges and shrapnel. As she passed the Old Head of Kinsale, a few miles down the coast from Cork, Captain William Turner slowed to catch the Liverpool tide and U-20 struck shortly afterwards. One of the finest ships then afloat went down in minutes. The British Government won the propaganda war which ensued and firmly denied that the ship had been carrying weapons of war. No one wanted to hear the German side of the row. The death toll would have been greater but for the fishermen and boat owners along the Irish coast who set out and plucked hundreds from the sea. They also brought in many of the dead, but William’s body was never found. It was 12 years later that his widowed mother Alice embarked on a trip to see relatives in Falls River which had been paid for by her family. She took a wreath with her and, as they neared the south coast of Ireland, she asked one of the ship’s officers whether they would be sailing anywhere near the Old Head of Kinsale. The officer said they would be and mentioned her enquiry to his captain who not only slowed the mail ship Celtic as they passed the spot where the Lusitania had gone down but he held a service of remembrance for William and all the others who had died in the tragedy. It was a poignant moment as the elderly and tearful

Mrs Dewhurst cast her wreath onto the waves. Anyone conversant with Darwen’s old cemetery will tell their friends that every grave and every headstone has a story to tell. William’s death is commemorated on a headstone at the Dewhurst family grave close to the old cemetery entrance. This, briefly, is his story.

Cemetery supervisor Billy Briggs shows the Dewhurst family grave headstone on which Lusitania victim William Dewhurst is remembered. The grave is the last resting place of his father John (d 1901), mother Alice (d 1945), his baby sister and brother who died in 1957. The grave is in Section H behind the C of E mound. It is visible from the narrow path down to the south lodge.

By Harold Heys February 2011