The once-elegant marble memorial stone to the Rev. Philip Graham, first vicar of St John’s, is now back to its white, shining best after a generous gesture from one of his relatives, Alistair Graham who lives in Kelvedon, near Colchester.

The Rev. Graham was his great, great grandfather.

Mr Graham saw an article by Harold Heys and Bill Taylor on the cemetery web site last summer and contacted Rosemary Jackson. Harold gave him a rough idea of what the cost might be and put him on to Brent Stevenson and the result is a wonderful addition to the north west edge of the cemetery.

Friends’ chairman John East has telephoned Mr Graham to thank him for his gesture.

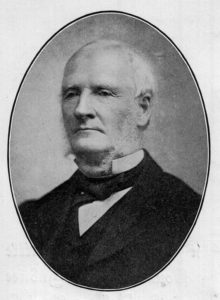

The Rev. Philip Graham

BEFORE Darwen Cemetery opened in 1861 it was usual for parishioners to be buried in church grounds. But after that date the municipal cemetery became the last resting place of choice for just about everyone.

Churchyards throughout the country were getting full up and the health hazards from many of the old graveyards were becoming a problem. New town cemeteries were badly needed and they were being opened throughout the country in the mid 1800s.

In Darwen there was, however, one notable exception to the new standard. When the Rev. Philip Graham died in the spring of 1887 he was buried not in the municipal cemetery but in his own churchyard. And there he lay for nearly 80 years.

The Rev. Graham, born in Cumberland, came to Darwen in 1851 as curate of Holy Trinity Church where he made quite a name for himself. In more ways than one.

He was friendly with Jane Brandwood, soon, in 1857, to be heiress of her father, uncle and brother who had all been coal merchants and mine owners, but she married widower Eccles Shorrock, a prominent cotton manufacturer and uncle of the man who later built India Mill. Shorrock died on July 23, 1853 after less than two years of marriage to Jane.

Turncroft Hall as it is today

The Rev Graham had been moved from Darwen in September 1854 to work as curate at St Marks’ Cheetham Hill and family and local historians reckon he was packed off to cool his heels and his ardour. He stuck it for about 15 months and then resigned his curacy, returned to Darwen, and, in the autumn 1855, married the grieving widow Shorrock who was by then already very wealthy.

No more tramping round the mean streets and slums of Manchester for Philip. The Grahams lived at Turncroft Hall in some style and she built for him the rather magnificent St John’s Church on Red Earth Road (as it was then spelt). It was consecrated in the July of 1864; St John’s School on Barton Brow followed two years later.

I spent nearly six years there as a child and remember the two school “houses” – Graham and Huntington which was named in honour of another prominent local family,

Mrs Jane Graham

Jane died after a long illness in the spring of 1867 and already Graham was heavily involved in politics and civic affairs. He was one of the founding fathers of the Conservative Party in North East Lancashire and was every inch the landowner and gentleman benefactor. After his death on May 10, 1887, there were glowing tributes to him in the local Press and in the Parish Magazine.

The memorial inside the church

The probable reason for him being shunted off to Manchester was not mentioned. Eccles Shorrock II had no doubt about the situation and it appears that he and his family were rather miffed that Graham had got his hands on a considerable proportion of the vast riches which might well have fallen into their hands.

Eccles Shorrock II wrote of Graham marrying his uncle’s second wife Jane” immediately after she was widowed” and added: “Rumour had it that the two had been well known to each other before she became Mrs Shorrock. With some feeling, he said Jane had “carried off a substantial legacy after less than two years of the marriage.”

His own mother had died and as a young man he wasn’t impressed with his uncle: “I cannot speak, even now, of my feeling when he took it upon himself to marry again so soon after Aunt Eliza died in 1850, who, though she had never wished me to call her ‘Mother’, had been a true parent to me, kindly, but firm, warm – natured, giving strongest encouragement to my endeavors, the perfect complement to uncle, who retained a certain aloofness.’

By 1869 Graham was so involved with his estate, local politics and various Committees that he gave up his living and was busy enlarging his list of prominent contacts.

The original headstone

There doesn’t appear to have been much love lost between Graham, Conservative and C of E and Shorrock, Liberal and Nonconformist. The Shorrocks were very well off industrialists, of course, but times change and within a few years they were descending into rather straightened circumstances. However, all that for perhaps another day.

Graham was buried in St John’s Church grounds, just on the north side. There was a fine cross with the line: “He feared God, he honoured the Queen, and he loved his Country.” Three years later his second wife Isabella paid for a

An early picture of St John’s and the vicarage

memorial in white marble inside the church. They had been married in London ten years after Jane’s death.

Special permission for the burial had to be obtained from the Home Secretary and it had to have the assent of the local authorities. The grave was consecrated according to a special form of prayer. It was quite an occasion. Everybody was there.

And that is where the Rev. Philip Graham, first vicar and founder of St John’s Church, man about town, benefactor and politician, lay in splendid isolation for the next 80 years….

In 1966, soon after the church had celebrated its centenary, dry rot was rampant in the church and there wasn’t the money for wholesale renovation. It was demolished and the first vicar’s remains and headstone were moved, on September 22, to a new resting place in Darwen Cemetery. You can see it today and you can still make out the inscription. But, of course, the elegant cross no longer sits majestically on top. Elf ‘n’ safety, you see. However, the cross isn’t damaged and sits neatly in the ground in front of the base.

(Above) The headstone before restoration.

(Above) The headstone after restoration.

Perhaps one day an entrepreneur or benefactor will find a couple of hundred pounds to clean it up and restore it to its former glory….

The grave is reached from the Lark Street entrance. Through the gates. Turn quickly to the right and follow the ragged asphalt path as it begins to curve uphill for about 40 yards. The grave is by the stone wall in the shade of the line of tall trees.

Tony Foster adds: The new church of St John’s did not have a burial ground attached because central government had instructed the Local Board of Health a few years earlier that all graveyards attached to the Darwen churches and chapels had to close for burials that required new grave plots. As the Darwen LBH took some considerable time to find a site and build the cemetery the cut-off date was put back a couple of years. There were Church of England graveyards at St James’ and Holy Trinity and at these Nonconformist chapels: Lower Chapel, Pole Lane Chapel, Belgrave Meeting House, Wesleyan Methodist Chapel in Belgrave Square, Redearth Road Primitive Methodist Chapel and Duckworth Street Methodist Chapel.

By HAROLD HEYS and BILL TAYLOR

February 2011

The headstone before we restored the Cross

Perhaps one day an entrepreneur or benefactor will find a couple of hundred pounds to clean it up and restore it to its former glory….

The grave is reached from the Lark Street entrance. Through the gates. Turn quickly to the right and follow the ragged asphalt path as it begins to curve uphill for about 40 yards. The grave is by the stone wall in the shade of the line of tall trees.

Tony Foster adds: The new church of St John’s did not have a burial ground attached because central government had instructed the Local Board of Health a few years earlier that all graveyards attached to the Darwen churches and chapels had to close for burials that required new grave plots. As the Darwen LBH took some considerable time to find a site and build the cemetery the cut-off date was put back a couple of years. There were Church of England graveyards at St James’ and Holy Trinity and at these Nonconformist chapels: Lower Chapel, Pole Lane Chapel, Belgrave Meeting House, Wesleyan Methodist Chapel in Belgrave Square, Redearth Road Primitive Methodist Chapel and Duckworth Street Methodist Chapel.

By HAROLD HEYS and BILL TAYLOR

February 2011